Getting φρίκη (phrikē)

Some spoooooky Late Antique & Byzantine finds

Halloween is one of my favourite holidays, at my favourite time of year. Although the Byzantines did not celebrate Halloween, which has its origins in Celtic religious and spiritual traditions, I thought it would be fun regardless to share some spooky and shivery (and, at times, funny) Late Antique and Byzantine figures, tales, and artefacts.

There are lots of well-known demon tales in the hagiographical archives of Byzantium, so I’ve avoided going in too deep on that front. If you’re interested in demons in Byzantine thought and literature, however, drop me a message — or hold out for an Exegesis piece on that topic in the near future!

And, in case you were wondering, the term φρίκη (phrikē) is an ancient Greek term describing the physical, unsettling sensation of goosebumps or shivering, where the physical sense mimics the yawning, growing fear felt within… maybe some of these objects or stories will induce φρίκη in some of you… or, perhaps, you’ll just get some very last minute costume inspiration.

Happy Byzanto-ween, you creepy creatures!

Bloody Mary, Bloody Mary, Bloody Mary! Magical Hematite (Bloodstone) Amulets

The use of magical amulets and charms was a common apotropaic (protecting against evil influences, spirits, or invisible forces) practice in Late Antiquity and Byzantium. This reflected the continuation of ancient Greco-Roman practices, but with the advent of Christianity, these ‘popular’ forms of veneration and self-protection were reframed through more ‘appropriate’ iconography: Christ, one of the Saints, or, very commonly, the Virgin Mary.1

Particularly favoured, seemingly by women for reproductive health purposes, were bloodstone amulets. Carved from the mineral hematite, which can occasionally have a blood-like appearance, as can be particularly clearly seen in the second image above, was believed to stop or increase blood flow — making it important for women during their fertile years, and during menopause.

Hematite amulets therefore reveal where material, form, and function came into collision in practices of making in the Byzantine world. They also provide some of the best insight that we have into the measures that women took to protect and enhance their own health, especially in the face of widespread male ignorance or disgust for the female body, even in the medical field.2

What is perhaps spookiest about this is how little has changed in 1,000 years — a fact many women who have attempted to seek medical attention for reproductive health issues will be able to attest to.

Some more freaky amulets for your viewing pleasure…

Taking care of the dead: the nekrotaphoi (νεκροταφοι) of the Great Oasis

A group of rather bizarre papyri from the 3rd and 4th centuries reveal the lives of several generations of nekrotaphoi living and working in Egypt’s Great Oasis. Who were the nekrotaphoi, you might ask? Well, simply put, they were undertakers, tasked with preparing the dead for their final journey to the underworld.

Fascinatingly, it seems that this was a profession passed down through the family line. It is clear from the papyrus archive that exists primarily in relation to the descendants of a certain Katamersis and a certain Polydeukes, who would have lived at the end of the 2nd to the beginning of the 3rd century. Polydeukes was a manumitted slave of Petosiris and Petechon, the son and grandson of Katamersis. The interconnected worlds of this wider familial network are revealed across three generations through the papyri, so too are their business dealings, issues concerning property, and general participation in wider Late Antique Egyptian society.3

There are three kinds of self-identification within this nekrotaphoi category that the papyri share with us: the nekrotaphos(m)/nekrotaphe or nekrotaphissa(f); the exopylites(m)/exopylitis(f); and the allophylos. The nekrotaphos/phe/phissa were the buriers of the dead bodies. The term refers to both grave-digging and the preapration of the body through the mummification process. This was a position that seems to have been well-paid.4

The exopylites/tis were those who ‘lived outside the gate,’ but who broadly engaged in the same activities as the nekrotaphoi.5 The terminology reflects the social stigma of professions associated with the dead in the ancient world, even in a place like Egypt, where the culture had traditionally been more accepting of death and the bodies of the dead.

The term allophylos, on the other hand, may apparently represent some kind of discriminatory term for the wider funerary profession. It may be the case that only the term nekrotaphos/phe/phissa actually denotes a professional association, while the other two reflect an ‘embedded social description.’6

Roman colonisation had lead to the Ancient Egyptian and Ptolemaic period’s relative comfortability with death being sidelined, and those who inhabited professions relating to the world of the dead were socially excluded and marginalised.7 This fascinating dossier, which I hope to post more extensively about in the future, reflects how a community on the margins of society, of the landscape, and of life itself, continued to engage with a world that deemed them strange and other.

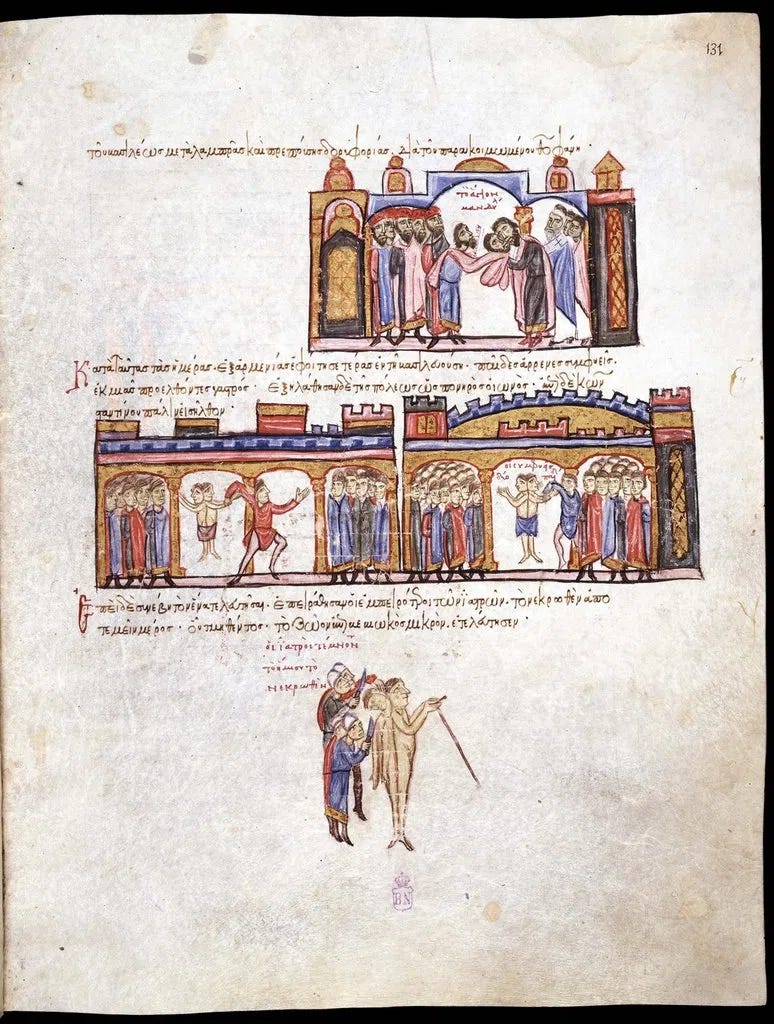

Seeing double: the case of the conjoined twins in the Madrid Skylitzes

The so-called Madrid Skylitzes is a 12th-century manuscript containing the Synopsis of Histories (Σύνοψις Ἱστοριῶν) of John Skylitzes, a Byzantine historian of the 11th century. John’s Synopsis covered the history of the empire from the death of Nikephoros I in 811 AD until the usurpation of Michael VI in 1057 by his wife, Zoe, and her sister Theodora. The manuscript is famous for its depiction of numerous Byzantine military events. This includes a vivid miniature showing the use by the navy of Greek Fire, the famed and feared Byzantine chemical compound that enabled fire to burn on water, unable to be put out.

Whilst the Greek Fire is a bit crazy, I’d argue that the Madrid Skylitzes contains some slightly more spooky and interesting illustrations and tales. That includes the tale of the conjoined twins of Constantinople. This tale was first attested to by Leo the Deacon, who speaks of a pair of ‘male twins, who came from the region of Cappadocia…’:

'I myself, who am writing these lines, have often seen them in Asia, a monstrous and novel wonder. For the various parts of their bodies were whole and complete, but their sides were attached from the armpit to the hip, uniting their bodies and combining them into one. And with the adjacent arms they embraced each other’s necks, and in the others carried staffs, on which they supported themselves as they walked. They were thirty years old and well-developed physically, appearing youthful and vigorous.’

— Leo the Deacon, History (quote taken from Medievalists.Net)

These twins were understood by some to be a particularly bad omen, and thus they were exiled from the city, before being brought back. It was at this moment that a horrifying (albeit, impressive, given the medical standards of the day) experiment was attempted. Following the death of one twin, Theophanes Continuatus, a chronicle of the 10th century, informs us that:

‘… skilled doctors separated them cleverly at the line of connection with the hope of saving the surviving one but after living three days he died also.’

Theophanes Continuatus8

This was the first ever surgical attempt at separating conjoined twins, and it would not be attempted again until 1689!

Although the Byzantines are frequently portrayed as a rigidly theocratic, religious, and un-scientific society, this story’s account of skilled doctors, of a briefly successful and immensely complicated surgery, and of the discourses around omens, disabled and/or othered bodies, and travel in 10th century Constantinople shows that this view is really overly simplistic. The Byzantines were curious, experimental people — even though they understood the world through a different prism to our own, post-Enlightenment paradigms.9

Lord of the Demons — Procopius’ Scathing Attacks on Justinian I

One thing that is good fun about 6th-century historian Procopius, a man who receives a lot of airtime on this Substack, is that he really is willing to go all in on shock and horror. He’s perfect Halloween reading, in that regard!

Here I offer you his take on some of Justinian I’s demonic tendencies….

‘Such, then, were the calamities which fell upon all mankind during the reign of the demon who had become incarnate in Justinian, while he himself, as having become Emperor, provided the causes of them. And I shall shew, further, how many evils he did to men by means of a hidden power and of a demoniacal nature. For while this man was administering the nation’s affairs, many other calamities chanced to befall, which some insisted came about through the aforementioned presence of this evil demon and through his contriving…’

— Procopius, The Secret History, (ed. and tr.) H.B. Dewing (Loeb Editions), 1940, p.223

More concerningly…

‘And that he was no human being, but, as has been suggested, some manner of demon in human form, one might infer by making an estimate of the magnitude of the ills which he inflicted upon mankind. For it is in the degree by which a man’s deeds are surpassingly great that the power of the doer becomes evident. Now to state exactly the number of those who were destroyed by him would never be possible, I think, for anyone soever, or for God. For one might more quickly, I think, count all the grains of sand than the vast number whom this Emperor destroyed. But making an approximate estimate of the extent of territory which has come to be destitute of inhabitants, I should say that a myriad myriads of myriads perished.

— Procopius, The Secret History, (ed. and tr.) H.B. Dewing (Loeb Editions), 1940, p.213

And, finally, of Justinian’s evils made flesh:

‘And some of those who were present with the Emperor, at very late hours of the night presumably, and held conference with him, obviously in the Palace, men whose souls were pure, seemed to see a sort of phantom spirit unfamiliar to them in place of him. For one of these asserted that he would rise suddenly from the imperial throne and walk up and down there (indeed he was never accustomed to remain seated for long), and the head of Justinian would disappear suddenly, but the rest of his body seemed to keep making these same long circuits, while he himself, as if thinking he must have something the matter with his eyesight, stood there for a very long time distressed and perplexed. Later, however, when the head had returned to the body, he thought, to his surprise, that he could fill out that which a moment before had been lacking. And another person said that he stood beside him when he sat and suddenly saw that his face had become like featureless flesh; for neither eyebrows nor eyes were in their proper place, nor did it shew any other means of identification whatsoever…’

— Procopius, The Secret History, (ed. and tr.) H.B. Dewing (Loeb Editions), 1940, p.151

Robo-Byzantium: Automata at the Court of Constantine VII (905-959)

This account comes from the travelogues of Liutprand of Cremona — a fascinating and really hilarious read — a courtier working first at the Lombard court of Berengar II and then for his rival, the Holy Roman Emperor Otto I in the 10th century. The important thing about Liutprand (for Byzantinists) is that he visited the Byzantine court, twice, and he wrote extensively about his trip.10

One of his more interesting digressions includes the entrance to the Byzantine throne room, where he says that he witnessed:

'…lions, made either of bronze or wood covered with gold, which struck the ground with their tails and roared with open mouth and quivering tongue…’

‘A tree of gilded bronze, its branches filled with birds, likewise made of bronze gilded over, and these emitted cries appropriate to their species…’

And he claimed that:

‘The emperor’s throne itself… was made in such a cunning manner that at one moment it was down on the ground, while at another it rose higher and was to be seen up in the air.’11

This is no blockbuster movie or graphic novel. This is a real account of what were essentially proto-robots, apparently populating the throne rooms of Byzantine Emperors!

The fascination with making automata was an ancient one, found in myth and legend, for example, in tales of Haephaestus and his automated humanoid workers. But these automata were not simple constructs of the imagination, but real things that ancient mechanics were able to create. The Islamic Abbasid Court was famed even by the Byzantines for its propensity to create beautiful, hydraulic-powered automata, like enormous trees with perched, singing birds — such as those that Liutprand references in his account.12

Put yourself in Liutprand’s shoes, for a moment. Not only are you entering the throne room of one of the most powerful men in the world, already intimidating enough, but then you’re confronted with a giant, golden lion that roars as soon as you take a step. I’d be shitting mysef!

What lies beneath…? Medusa in Constantinople

Perhaps one of my favourite examples of the Byzantine love of spolia can be found in the so-called Basilica Cisterns in Istanbul. Spolia describes the practice of reusing older architectural features in new structures, often preserving something of the original design or structure of the feature being repurposed.

The Basilica Cistern was constructed deep below the city of Constantinople during the reign of Justinian I (527-565 AD). The space itself is massive, capable of holding some 80,000 cubic metres of water. There are over 300 marble columns supporting the arched ceiling — which, if you know anything about quarrying marble, would have meant an awful lot of time, money, and energy to get brand new stones into the city of Constantinople.

Luckily for Justinian — or, more accurately, for the 7,000 slaves who actually constructed the cistern — Constantinople was a city built on ancient foundations. There were plenty of pagan temples still lying around the city, ready to be refashioned into something a little less pagan-y — not to mention the temples still in existence across the rest of the Empire.

Lo and behold, someone at some point stumbled upon two massive heads of the Gorgon Medusa, and decided that these blocks would make the perfect foundation stones of two of the marble columns in the cistern. Curiously, however, they chose to turn them sideways and upside down, rather than turning them upright.

It is this choice that has lead to the assumption that these heads were deliberately chosen to be hidden away down in the depths of the city, inverted so that they could not release their terrible, polytheistic powers by corrupting the water supply or causing the ceiling to collapse. It was a commonly held belief in Late Antiquity, and into Byzantium, that pagan cult statues retained a presence in their being. Not the (hopefully) beneficent spirit of a god, as supposed by their Greco-Roman ancestors, but a demonic force, who had to be tamed or rendered powerless, occasionally through the destruction or adjustment of a statue.

Alternatively, the presence of these Medusas may represent a continued belief in old, apotropaic functions that they once held for ancient people. Rather than themselves harm the water or the cistern, perhaps they were there to ward off forces which might do so.

What I find the most interesting is the sense that, for some reason, it was thought to be better to preserve these objects than to destroy them outright. By hiding them away, beneath the ground, the builders of the cistern ensured that whatever power they held within them remained in Constantinople… but buried, waiting in the watery quiet, for a thousand years until their rediscovery…

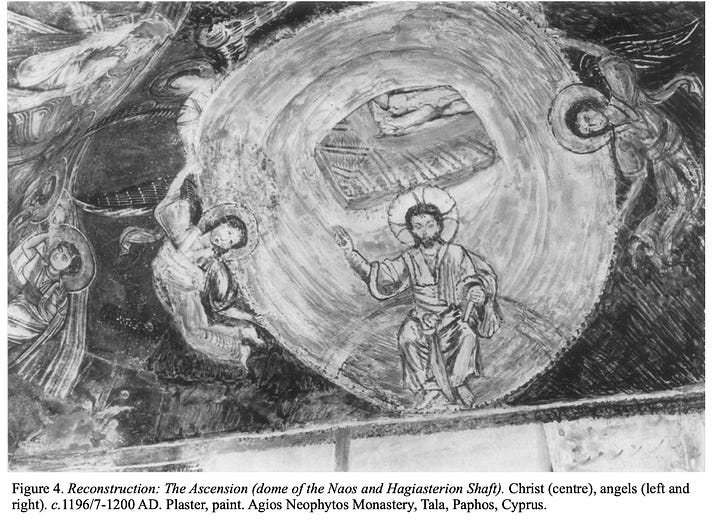

I always feel like… somebody’s watching meee: St. Neophytos the Recluse of Cyprus & the Enkleistra monastery

Cyprus in the Middle Ages was kind of an odd place. It had changed hands a couple of times, going from the Byzantines to the Arabs to the Crusaders to the Knights Templar, who bought the island for a pretty penny from Richard the Lionheart. There were numerous tax revolts, and the local population was fairly unhappy with the state of affairs — not only raised taxes, but piracy and general violence, and probably just being bought and sold like cattle.13

In the midst of the chaos of the late 12th and early 13th century, an especially bizarre man found himself wandering around Cyprus, trying to get to Jerusalem. This was the man who would eventually become Saint Neophytos, a ‘hermit’ who founded a monastic community around his cave sanctuary, the Enkleistra.14

What remains of the Enkleistra and Neophytos’ order of monks is a very interesting typikon, or a monastic foundational document, which laid out the order’s rules and regulations, and a series of fantastical, but rather strange, wall-paintings.15

What was so strange about these wall-paintings? Well, it wasn’t so much their content or design, which were quite typical of the time, but the emphasis that they placed on their founder’s apparently pre- and self-determined sanctity. In case you didn’t know, it wasn’t usually done for someone to decide themselves that they were a holy man or woman. They might have thought it, certainly, but it was usually up to a follower, a disciple, or other interested parties to actually sanctify them.16

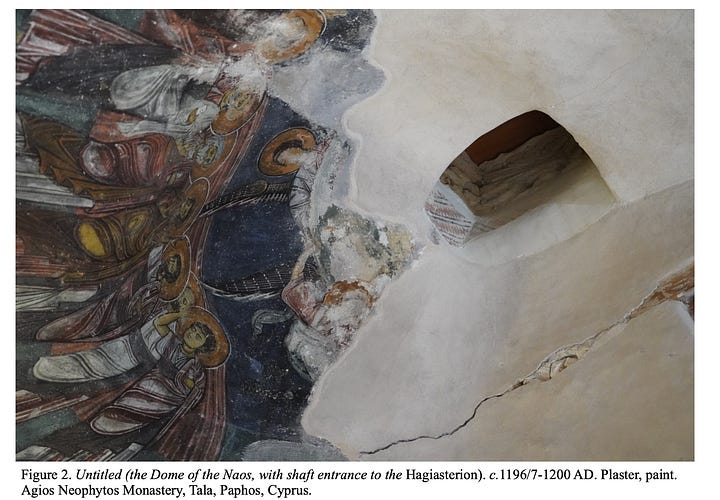

But Neophytos was a kooky guy, and he decided to portray himself in his wall paintings as already a Saint. That included a depiction of him seemingly being lifted up into heaven by angels, the cross of their wings at his back almost resembling a pair of wings for himself, and a notably odd architectural feature within the cave monastery itself.

Towards the end of his life, Neophytos truly became a ‘recluse,’ choosing not to interact with the now quite large order of monks who followed his word. But he did decide to build a personal cell right above the ‘dome’ of the church. And, disturbingly, he cut a whole in the bottom of this cell, which allowed him to look down upon the monks in his order during liturgical services, without them necessarily knowing he was watching them from above! Presumably, he wished to reprimand their bad behaviour by catching them unawares.

How did Neophytos make sure his monks could never quite tell if they were being watched or not? Well, he had some wall paintings done on the dome’s ceiling, too. The iconography was pretty standard — Christ ascending into heaven. Except for the fact that Neophytos had Christ painted so that his head and neck went up into the shaft leading up to his cell. Which meant that, if a monk was to look up and catch a glimpse of Neophytos looking down at him, it would appear as though Neophytos’ head was upon Christ’s body — no doubt, giving the monk a real fright for a moment, when ‘Christ’ actually moved and blinked as he observed him!

Thanks for coming along on this phrikē journey into some spooktacular Byzantine tales, objects, and people! If you’re interested in some Byzantine Ghost stories, then I’d recommend heading over to the Byzantium and Friends podcast, where the episode ‘Byzantine Tales of Horror and the Macabre’ will satisfy all your terrible desires…

Byzantium was a very scary place, so next year’s edition of Getting φρίκη will have even more hair-raising content… keep an eye out. Or, better, your wits about you!

Once more… Happyy Byzantooweeeeeeeeeeeen!

Mecerian, J., Mouterde, R., “Objets magiques. Recueil S. Ayvaz”, Mélanges de l’Université Saint-Joseph (Beyrouth, Lebanon) 25 (1942-1943), pp. 105-128

J. Poole, ‘Menopause and Agency in Late Antiquity: A Case for Magical Gems,’ in eds. S. Panayotov, A. Juganaru, A. Theologou, and I. Perczel, Soul, Body, and Gender in Late Antiquity: Essays on Embodiment and Disembodiment (London: Taylor & Francis, 2022)

R. Bagnall, The Undertakers of the Great Oasis (P. Nekr), (London: The Egypt Exploration Society, 2017), pp. 4-5

R. Bagnall, The Undertakers of the Great Oasis (P. Nekr), (London: The Egypt Exploration Society, 2017), pp. 7-8

R. Bagnall, The Undertakers of the Great Oasis (P. Nekr), (London: The Egypt Exploration Society, 2017), pp. 7-8

R. Bagnall, The Undertakers of the Great Oasis (P. Nekr), (London: The Egypt Exploration Society, 2017), p. 8

R. Bagnall, The Undertakers of the Great Oasis (P. Nekr), (London: The Egypt Exploration Society, 2017), p. 9

In G.E. Pentogalos and J.G. Lascaratos, ‘A Surgical Operation Performed on Siamese Twins During the Tenth Century in Byzantium,’ in Bulletin of the History of Medicine 58 (1) (1984), pp. 99-102; p.99

An open access article which will be of interest to those taken by this tale: K. Zamora, C. Da Rocha Birnfeld, and A. Barrios, ‘A Medieval Surgery, Illustrated: The First Recorded Surgical Separation of Conjoined Twins’ READ HERE

Liutprand of Cremona, Relatio de Legatione Constantinopolitana (10th century) - Internet Archive link HERE

L. Safran, Heaven on Earth: Art and the Church in Byzantium. (Pittsburgh, PA: Pennsylvania State Press, 1998), p. 30

For a quick read about Abbasid automata, check out THIS ARTICLE

Coureas, N., ‘The Conquest of Cyprus during the Third Crusade According to Greek Chronicles from Cyprus,’ The Medieval Chronicle, vol. 8, (2013)

The (only) expert on St. Neophytos: Galatariotou, C., The Making of a Saint: The Life, Times, and Sanctification of Neophytos the Recluse, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991)

For analysis of the wall-paintings: I. Kakoulli and C. Fisher The Techniques and Materials of the Wall Paintings at the Enkleistra of St. Neophytos (Phase II)