The black, beady eye, marked by a reflective glimmer in its centre, draws my own towards it. A raised hoof, maybe readying itself to gallop, maybe stamping the ground to indicate a challenge, thrusts forward into the blank white space between us. The boar might have a smirk on his face, like he senses my trepidation. Or, perhaps, the trepidation of trespassers past, those who have already been bested.

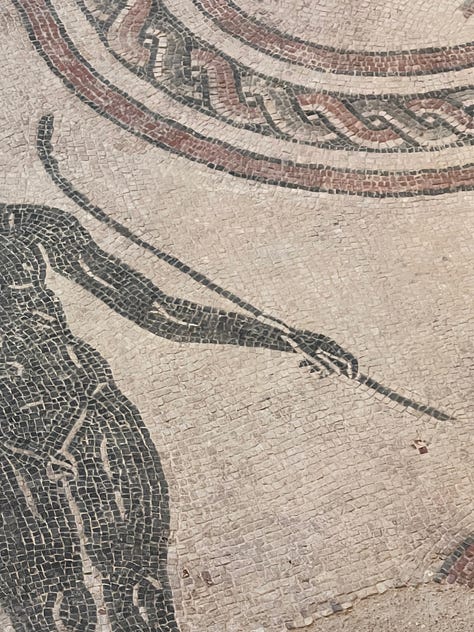

This boar is a shadow, an imprint rendered in tile. His back half is destroyed, the tiles lost to time. The front half of his body gives the impression of forward motion, the etchings of rustling hair and bristles are marked out by subtle white gaps between deeper black tiles. But he charges forward only into the red circular border of his enclosure, the mosaic medallion. His forested habitat is reduced to a line of beige and red tesserae and, behind him, a permanent, blank white. The boar is alone in his mosaic world, circumscribed and decontextualised by the possessors of his image, the commissioner of the mosaic and the owner of the villa, as well we who observe him across time and space. I am stood looking at him at the Villa dei Mosaici di Spello, an archaeological site some thirty minutes drive south of Perugia, Umbria.

The villa was unearthed in 2005, when contractors building a carpark stumbled upon the complex, still covered with a vast and mostly intact sea of black, white, and red mosaics. There are geometric, abstract designs of interlocking chains and weaves, repeated sun or floral motifs. There are hosts of creatures, which we can confidently identify because of the artists’ convincing portrayal of species-specific features. There are personifications of the seasons rendered alongside the animals, within the sparse white background that makes their landscape. According to the information boards, the villa has two phases, Augustan (1st century AD) and Late Imperial (c. 2nd - 3rdcenturies AD). Helpfully, the archaeological museum does not see fit to specify which sections of the villa can be dated to which section, other than stating that the mosaics are definitely Augustan. I can only assume that the later phase was either constructed on top of the villa structure currently present and then removed during excavation to reveal the ‘finer,’ earlier work beneath, or that the second phase was an extension of the original villa outwards, which has not been included within the museum’s purview because it does not contain enough elements of interest to justify public viewing. I do hope it is the latter.

Before setting out to Spello that morning, I was awoken by the sounds of shots echoing across the valley. When the shotguns fire, they reverberate over the hills. Because of this, you’re never really sure if the hunt is taking place in the dense thicket immediately below you, or if they are tracking an animal in a more distant wood. Such is the nature of the chase for the cinghiale, where hunters race barely-road ready vehicles up and down the Strada Bianca, clad in fluorescent orange and yellow camouflage. This may seem contradictory to the aim of disguise, but apparently boars are unable to see fluorescent colours. And, importantly, humans are able to — there is no shortage of rumoured incidents of shotgun rounds fired at someone, rather than something.

History is, by definition, the human story. We are someone and everything else around us is something. It necessitates the study of a past that is viewed through our species’ eyes. Those members of our species that we engage with through the written, visual, or material records may well be vastly different from us; they undoubtedly existed under different cultural paradigms, they probably experienced different stresses and tensions, they may have been accepting of ideas and dicta that appear strange, foreign, or even outright wrong to us. But, at the end of the day, we structure our engagement with the discipline through an unending chain of human retinas and optic nerves, in a way that feels somewhat comforting.

What happens when we direct our gaze away from our own experience? When we resist the solipsistic and interior nature of both the study of ourselves and also, typically, the way that we think about ourselves? The answer is not straightforward, because ultimately everything we think and do must be expressed through our language, and thus through our own experience to some critical, terminal degree. However, with the translation of ideas from anthropology into the historical field, like Clifford Geertz’s ‘Thick Description,’ and Alfred Gell’s notions of artistic and object agency, there has been since the nineties a rise in histories that deal with non-human historical experience (Geertz, The Interpretation of Culture: Selected Essays, 1973; Gell, Art and Agency, 1998). We say these histories have been produced under the ‘interpretative turn,’ the ‘material turn,’ the ‘object turn,’ and, increasingly, the ‘animal turn.’ We are beginning to accept the limitations of the prism of our experience, whilst trying to use our capacity for expression for the widening of the historical field.

However, analysing sources or building sustained historical arguments on the basis of non-human creatures, plants, or the objects that we use, having any form of agency is fundamentally challenging. Firstly, mentally engaging with the proposition that these beings and things, which we have been programmed to view as passive recipients of human whims and wiles, takes a lot of initial imaginative leaping. This is especially the case in a highly consumerist culture, where, whether we like it or not, we are largely viewing the world as our own personal resource well, where everything is fair game to be exploited. Secondly, the actual theory is dense and complex, requiring you to read it multiple times to understand it, then return to your sources multiple times to apply it differently and under different conditions, to the extent that you sometimes begin questioning the very nature of reality, the force of anachronism and the limits of your intellectual capacity fraying the threads of time and space. Finally, trying to explain as academic historians to anyone else that you are investigating the histories of things that either have no consciousness, or, if they do, it is a contested and debated matter, and, more problematically, the subjects that we are looking at are unable to express it to us, is often met with a gentle confusion at best and a sneer at worst.

Is this really what we keep funding the humanities to do?

With this being said, all new modes of thinking and ways of being bring challenges with them, especially when they run counter to traditional, capitalist logic, which stresses a progressivist or determinist historical timeline that leads ‘inevitably’ to our current ‘utopic’ temporal situation. The idea that we would look at things or animals or plants as conscious forces or active agents has echoes of traditional indigenous knowledges from across the globe, the likes of which Western ‘progressivism’ has long been trying stamp out. However, the fact is that turning away from human retinas and trying to transplant ourselves into non-humans is wildly helpful for asking new questions where research may otherwise go stale. It provides new ways of seeing the past, not as linear or inevitable, but as a layered structure that exists in various states of harder borders and more permeable ones. It both connects us more closely to history as subject and makes it easier to see where history must be object.

Hispellum/Spello is a case in point. As an insufficient overview of the town’s history, it was first settled some 7,000 years ago at the height of the Iron Age, then rose to prominence as a major centre of the Etruscan civilisation. The Etruscans were brought to heel with the rise of Rome in the 200s BC, but the town continued to flourish and maintain a distinctive connection with its landscape and its history even under the Republic and into the Empire. It was treated favourably under Augustus (under whose reign the construction of the mosaic villa is dated to) because of the town offering its backing to him during the Perusine War (41-40 BC). Thanks to Augustus, the newly minted Colonia Julia Hispellum was granted further territory in its immediate region and clearly received enough investment through imperial largess to undertake an extensive, monumental building programme.

It is most notable, however, for a period of history usually maligned by classicists and treated with some trepidation by modern historians: the Late Roman state. For, this is the site where, in 1733, a marble tablet was unearthed detailing a legal provision — called a Rescript, in response to a petition lodged by Hispellum’s inhabitants — from the Emperor Constantine I. It states that in c. 335 AD, Constantine and his sons had granted permission to Hispellum’s inhabitants to update and host an annual festival of gladiatorial games and theatre, to construct a new shrine dedicated to Constantine, and to rename the city after Constantine’s dynasty (Flavia Constans). The only restriction placed upon the city was that it did not ‘pollute’ the shrine in Constantine’s name with any ‘contagious superstition’ (Van Dam, The Roman Revolution of Constantine, 2007, p.29). This last element is ambiguous, but is frequently taken to refer to a prohibition on animal sacrifice, as had been standard at Roman polytheistic religious sites and during festivities.

The town is undoubtedly of interest to any scholar of Constantinian politics and religion. The issuing of the Rescript at a relatively late date in Constantine’s reign (he died in 337 AD), after the foundation of Constantinople and long after the Emperor’s supposed conversion to Christianity in 312 AD, has proven problematic for our traditional understanding of Constantine’s reign, for the spread of institutionalised Christianity, and for the nature of polytheism during and after the Constantinian era. But I am less interested in any of these problems than I am in what the layered history of the non-human entities in this town and in this region can tell us about, about ourselves and about the ways that history expands and contradicts itself, constantly.

To me, the Rescript is of interest because of its implication for the relationship of humans to animals, if we are correct in assuming that the ‘pollution’ the Rescript speaks of was animal sacrifice. The historian Lynn White Jr. wrote, in 1967, a piece for the journal Science entitled ‘The Historical Roots of Our Ecologic Crisis.’ This foregrounded Judeo-Christian religious ideals, particularly Western Medieval Christianity (‘Latin’ Christianity), as the major force lying behind the West’s exploitation of the natural world (White, 1967, pp.9-10). In one of the more interesting pieces of evidence he employs, he looks to Frankish harvest calendars of the 830s. He argues that prior to this, the artistic convention for portraying the months or seasons was to show them as ‘passive personifications’ (White, 1967, p.8). However, the ‘new style’ shows ‘men coercing the world around them — plowing, harvesting, chopping tress, butchering pigs. Man and nature are two things, and man is master’ (White, 1967, p.8).

White’s work kicked off the ecological revolution in the humanities. The argument that people in the Christian, Medieval West can be held uniquely responsible for the present-day ecological crisis was truly revolutionary. It is also wildly simplistic and contrary, I believe, to the kind of history that investigating nature as an historical agent actually presents. The Hispellum Rescript is but one example of how the nature of man’s relationship to nature was reconfigured under Christianity. The fact that the ritual sacrifice of animals was outlawed would have had a significant impact on the ways that people viewed animals, for one. More importantly, it also would have impacted the actual lives of generations of creatures themselves. Animals continued to be killed and used for meat, of course, but it would be a long time before the kind of industrial slaughter of animals that ritual sacrifice allowed became possible again — essentially with the advent of the factory farming industry in roughly the late nineteenth-century (Braddock, Implication: An Eco-Critical Dictionary for Art History, 2023, pp.11-13).

We can therefore posit with some credibility that the overall animal experience in Umbria, primarily for sheep, bulls/oxen, and goats, was enhanced by the issuing of the Hispellum Rescript. On a broader scale, it is emblematic of the beginnings of the phasing out of animal sacrifice throughout the empire. From this, we can extrapolate that the wider emotional experience of animals shifted under the Christian paradigm, and that this continued into the Medieval period. This does not dispute White’s thesis, but rather shows that there are nuances to the argument that Christianity’s advent had an overwhelmingly negative impact on the natural world.

Moreover, we can see that on the other side of White’s thesis is the implication that under the polytheistic regimes, at least in the West, nature was ‘less’ exploited. White, as an historian of technology, does also construct the basis of his argument upon the development of the plough, which he centralises alongside the Christian worldview as the chief facilitator of the ‘present-day’ ecological crisis. Again, I won’t dispute this, as I am no historian of technology. But, I will dispute the notion that prior to this man is suggested to have been part of a more integrated system rather than viewing himself or acting as a ‘master’ of nature.’ It seems that the mosaics at the Villa dei Mosaici tell a different story. The boar is not the only animal portrayed circumscribed by a border of red and decontextualised by the blank, white background from his natural habitat. A host of creatures both local and exotic, including deer, cheetahs/leopards, lions, waterfowl, hares, and what seems to be a sea-monster, are circumscribed and trapped within these mosaic medallions. The abundance of animals stuck in these perpetual holding cells suggests a desire to enact this ordered reality upon the real, animal world.

Then, at each of the four main corners of the mosaic floor, between the animals, are the seasonal personifications. In contrast to what White argues about the passivity of such representations, in contrast to his later Frankish calendars with their technologies of exploitation, these seasons themselves hold implements of natural extraction. Still clearly visible are Winter and Summer, with Winter holding a hoe and Summer a scythe. The personifications of Autumn and Spring are too damaged to make out, but we can see that they, too, held some kind of tool for working the land. Does this not indicate a similar state of affairs to White’s Frankish calendars? In the act of personifying the seasons, is there not also a suggestion of man as master? It seems that personification in and of itself is quite an active gesture. If we conceptualise of vast and strange concepts like the evolution of natural time through the guise of ourselves, are we not saying that we are in control of such forces, because we envisage them as versions of us?

Further, in the portrayal of a natural world that is divided and thus harmonised over an extensive floor surface, I would argue that the commissioner of the mosaic was making a strong statement of control and management over the forces being represented. When he and his audiences — whether they were family, friends, colleagues, or the servants of the household —walked through the space, they would have been aware of their position stood quite literally over Nature. More than this, the act of re-representing the natural world, the management of the chaotic existence of creatures great and small, trees and plants and rocks and hills beyond the walls of the villa, is an act of domination through familiarisation and ordering. It shows that man possesses the power to bring Nature within and to circumscribe it, to reduce its awesome power. The creatures that leap and run endlessly through blank space are no longer the fearsome enemies of the hunt or the imagined mythologies of danger that threaten long voyages over land and sea, but part and parcel of normal domesticity. Man’s domesticity. Couple this with the presence of the actual domesticated creatures that would have formed part of the ecosystem of the villa’s property, many of which were perhaps bred specifically for the acts of ritual slaughter outlawed by Constantine, and it is possible to see a world, prior to Christianity’s rise, in which man’s view of nature is just as damaging and exploitative.

The boar that so enraptures me does so also because I am familiar with him beyond his represented image. With every boom of a shotgun in the valley, I’m reminded of the fact of boar-hunting as an everyday reality of Umbrian rural life. I can imagine clearly the rising fear of the boars roaming the hills with the echoes of the rounds and the barking of the dogs. My own base, animal instincts cause me to jolt when I first hear that noise in the mornings, half-awake, even though I know exactly what the sound is, and that I am safe. Those very same boar nervous systems would have been stoked to fear by the barking of Roman dogs and the thwick of arrows flying through the forest. The boar that is represented in the mosaic was rendered so well, in such a lifelike way, because the humans who rendered him had likely seen his mutilated form at one point or another, brought back from a triumphant hunt with those same arrows sticking out from his thick hide.

Obviously, hunting has continued as a practice and a fact of life in Umbria from polytheism into Christianity. It was probably a fact of life in that initial, Iron Age settlement at Hispellum/Spello some 7,000 years ago. I am not advocating for the ending of longstanding traditions of management of the natural environment here. I am not a perfect advocate for animal rights, no sanctimonious preacher of veganism. I am trying, this year, to be a more mindful and ethical inhabitant of Earth by reducing my meat intake, both for the sake of animals kept under immensely cruel conditions for our consumption but also for the ravages upon Nature as a whole from industrial farming, but in this I am nowhere near perfect. What I am trying to say is that we ought to re-consider how we bring other beings and things into historical and modern conversations. By doing so, we can re-shape our own thought patterns, our relationships to ourselves and to other beings, and we can, I think, bring ourselves closer to the worlds of the past that we wish to study.

By recognising that the boar I am viewing, 2,000 years after its immortalisation in tile and stone, is the same boar that was hunted by Roman arrows and which is now hunted by Umbrian shotguns, I am positioning myself as an active agent of history alongside the agency of the boar, real and represented. The boar is not a passive creature, and the artwork is not a passive receptacle of the human experience. Of course, everything I’ve said here is an interpretation, mine alone. But these interpretations are being shaped by the agents I am interacting with as much as my interpretation shapes their existence. We exist symbiotically. Non-human and human blur into one another and transcend the humdrum of the modern world.

I do not think that White was ‘wrong,’ per se, in his assessment. I think that he was vastly ahead of his time, and I am forever appreciative of the fact that his paper brought the Medieval world closer to ours. By emphasising the technological advances connecting us through the shared linkage of natural exploitation, he was not only a forefather of the modern environmental movement, but a forefather of the deconstruction of the idea of the ‘Medieval.’ But the problem is that he still, quite fundamentally, centred the human story and wrote a linear history based on this centralisation. But this is not just the human story. This is also the animal story. The plant story. The objects of use story. Nature’s story. It may seem daunting to reckon with the sublimity of that, with the vast and sheer force of Nature, and I think it is conceptually easier for humans to position ourselves as dominant players in this wider drama rather than face up to the truth of our startling insignificance.

Therein, perhaps, lies the basis for the importance of animal sacrifice in Roman polytheism: sacrifice to the gods, who in turn control Nature, but humans are able to bring them and Nature to heel (to an extent), by performing their violence against living manifestations of the natural world. It is in turn the basis for thinking about the Hispellum Rescript banning animal sacrifice: Nature is pollutant, it must not be brought into the spaces of human worship, because humanity is holier than Nature; humanity is above Nature. That idea goes on to form some of the key tenants of Western and Eastern Medieval Christian thought. It subsequently forms the basis of the Renaissance and the Enlightenment, with the valuing of reason and logic and scientific experimentation over listening to or interpreting ‘irrational’ Nature. It is, furthermore, the impetus behind the very specific portrayal of the boar and his companions at the Villa dei Mosaici. They are so vivid and lifelike so as to be astonishing, clearly evoking the realities of the creatures they represent, and yet they are penned-in, in a way that their living compatriots could never truly be. But it comforts the villa owner, as it comforts us today, to imagine that they might be, in some alternate reality (the domestic space) where man is dominant.

In this framework, the progression of history is not linear. Instead, it builds upon itself but also elides itself, meaning that, if we only look through human eyes, we only view the strata currently sat on top. We miss the multifarious possible layers beneath. With the transcendence of this that comes from looking through the animal eye, not just staring down into it, I am trying to access these otherwise-elided strata.

The animal eye framework — or maybe it should be called the Natural eye framework, I don’t really know — also assists in providing Art History with a new, necessary relevancy. The discipline is frequently insular, closed off to outsiders without knowledge of the jargon and technical terminology, and the extensive corpus of convoluted literature. Because of the societal devaluing of the arts over the past fifty or so years, it has faced accusations of uselessness. But, in truth, the production of art and all associated objects is humanity’s greatest achievement. It is where we actually distinguish ourselves from the other creatures and things that inhabit this earth with us, and indeed from Nature itself, because only we possess the tools to view the world and represent it back to itself and to ourselves.

Paradoxically, then, it is where we subsequently must deal most directly with our non-human relationships, because it is with and through them, both through their representation and the use of their skin, hair and fur, eggs, waste products, and pigmented excretions that we are able to create our art and objects. As much as the objects have agency because of the values that humans project onto them, they have agency because of their formation as a result of those aforementioned features. In a sense, the artist’s eye is the animal eye, and vice versa. More than that, through art, the human eye is always looking to and for the animal eye.

Back in Spello, the black beady eye glints mischievously. The half-grin again offers me a challenge. I wonder if, when the artists had stared down those eyes as the boar was brought in from the hunt, they had realised that they could not create without the presence of his eye, without the presence of his foreign consciousness, still floating about somewhere in the ether.